591st Engineer Company (Light Equipment)

by Mark Sigrist

Author’s Note When Sp4 David Flinn arrived at his assigned unit in Vietnam in 1968, his first thought was, “There is nothing ‘Light’ about this Company.”

I have Dave considered my brother for 65 years. He and I talked about doing this write-up during a hunting trip in October 2018. He wanted to give a bit of history to his sons and grandchildren.

The photos were all taken by Sp4 David L. Flinn in 1968 and 1969. They’re certainly not of professional quality, but do tell the story from the point of view of a self-described “equipment operator.” One of Dave’s regrets was that most of the photos he took were lost a few days before his DEROS (Date Expected to Return from Over Seas) as a result of a rocket destroying his bunker (he was on the perimeter berm), so the photo story is somewhat incomplete.

Vietnam veteran, Sp4 David Flinn, 591st Engineers, left us with this photographic record of his unit’s activities in the A Shau Valley. While not professional shots, they provide a unique look into the daily activities of combat engineers. Here, Dave photographed this staging area that shows, right to left, an M123 10-ton tractor attached to M15A1 40-ton trailer, M37 3/4-ton truck, unidentified apparatus on wheels, batch concrete mixer on wheels, and unidentified.

Intro to the 591st Engineer Company (Light Equipment):

Dave’s unit, the 591st Engineer Company (Light Equipment) was part of the 27th Engineer Battalion (Combat), 45th Engineer Group (Construction), 18th Engineer Brigade (the parent unit for all Army engineers in Vietnam). Dave was a certified welder before induction into the Army. After he completed basic training at Fort Knox and was granted the welder MOS with no further training. Upon arrival in-country, the Company CO (commanding officer) asked Dave if he could drive heavy equipment — since he was a farm kid. On the affirmative, the CO promptly assigned him operate Caterpillar D7s. The CO needed an operator more than he needed a welder! Regardless, Dave got more than just a little time on the welder and twisting wrenches to make repairs.

One platoon of the 591st was had a portable rock crusher assigned for quarry/crushing operations. The 591st rock crusher platoon established and ran a quarry located at Phu Loc. In addition to supplying aggregate for Highway Route 547, the rock crusher supplied material for road improvements for much of I Corps and as far north as the demilitarized zone (DMZ). Dave’s construction platoon was equipped with Caterpillar D7 dozers, Clark 290M 20-yard scrapers, and related miscellaneous machines. Other elements of the Company included the maintenance platoon that was responsible for repair and maintenance of all the equipment; a transport unit for moving equipment and supplies; and the headquarters platoon that was responsible for logistics and all the care, feeding, and paperwork of the company.

Well-worn Caterpillar D7 undergoing maintenance near Firebase Blaze in 1968. Note M151 jeep alongside.

The Mission:

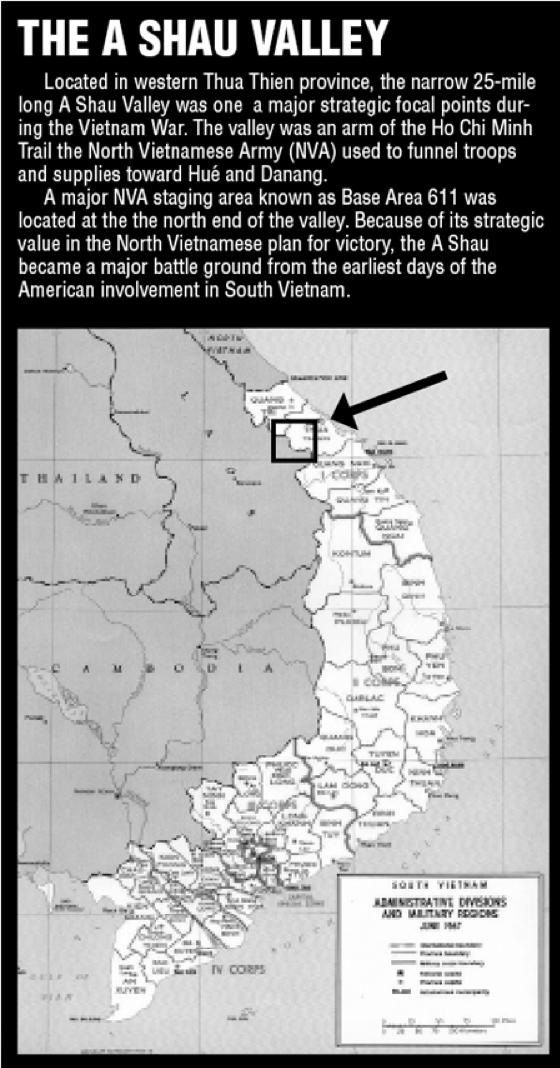

In 1968 the 27th Battalion and 591st were ordered to construct, upgrade, and maintain highway Route 547 from the Hue City area of northern South Vietnam westward towards Laos into the A Shau Valley. At that time, A Shau Valley was a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong (VC) stronghold. The mission also included establishment and construction of firebases, helicopter and artillery revetments, and other facilities along the route which went over and through the dissected landscape of mountains and small valleys. The mission was in support of the 101st Airborne Division’s efforts to deny the enemy of a “safe haven” area, logistic dumps, and communications (supply) routes, that is, a leg of the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

In effort to reduce risks to hostile fire, heavy airborne applications of defoliants (which later became be known as “agent orange”) covered wide swaths of the route way and potential firebase locations. Unfortunately, many of the engineers and others serving alongside are still suffering from the effects.

6×6 machine shop truck with gull wing doors alongside temporary work area with troops working on an undefined project.

Construction:

Caterpillar D7 dozers led the way, clearing and initially shaping the ground for the roads, bases and revetments. Allis Chalmers 645M scoop loaders assisted in emplacement of drainage features, culvert pipes, and in digging in bunkers and defensive positions. 380 horsepower Clark-Michigan 290M scrapers with 20-yard pans moved dirt and Caterpillar Model 12 graders leveled the terrain to standard. A rock drill and an American Hoist Model 2380 20-ton Rough Terrain Crane lifting a bucket or a pile driver were occasionally used to clear rock formations and stabilize stream crossings. M51 series dump trucks hauled aggregate and dirt.

Sign on Highway Route 547 announcing construction by the 591st Engineer (Light Equipment) Company near the northern Vietnam city of Hue leading into the A Shau Valley.

Although the intent was to keep the roadway at less than 6 percent slopes, some locations were well in excess of the prescribed slope due to the mountainous terrain. As the operations moved forward, the engineers built laager-type areas to be used as mini-bases for logistic, staging, and maintenance. Security could also pull back into these areas at night.

These major effort-type of operations required a huge amount of support and supplies. Convoys of M35 and M54 cargo trucks, M131 fuel tankers and M127 semi-trailers were constantly on the road hauling everything from rations and spare parts to barb wire, ammo, and explosives. The motor pool/maintenance guys and their equipment closely followed the dirt movers. Their vehicles included shop vans, M56 contact maintenance trucks, wreckers, and an M578 light recovery vehicle.

The typical procedure for establishment and development of night defensive positions up to and including complex fire support bases had similar protocols. First, the D7 dozers would clear the trees and taller vegetation. The dirt pans, front-end loader, and graders would join the dozers in leveling and shaping the terrain and digging in fighting positions, trenches, bunkers, artillery and mortar positions, ammo storage points, vehicle parking and maintenance/repair areas, and drainage features.

Usually, they would establish a helicopter LZ (landing zone), as well. The dozers would push earthen berms around the perimeter of the base. If the terrain would allow, vegetation outside the perimeter would be pushed back as much as 200 meters — for obvious reason. Concertina wire, barbed wire, claymores and land mines would ring the perimeter beyond the berm.

Rock crusher site with D7 dozer and heavy rock truck. Dave could not remember the origins or nomenclature of the rock truck.

Typically, bunkers were completely underground. If not, partly above ground and covered with sandbags or dirt. When a bunker was left completely above ground, the engineers would completely surround it (including the roof) with multiple layers of sandbags.

Longer-lived bases usually had various sizes of tents or even more traditional wooden buildings. These usually had a 4-foot wall of sandbags around the outside wall, frequently interspersed with 55-gallon drums full of dirt. Every Vietnam veteran had more than enough on the job training filling sandbags.

Occasionally, observation platforms or towers would be constructed. Infrequently, these observation towers would be equipped with a searchlight.

Tents and bunkers being established along the highway. The platoon is filling sandbags — a seemingly never-ending chore that everyone complained about doing but frequently were very glad to have for cover.

Shower points were established, usually using excess metal shipping containers or 55-gallon drums filled with water and placed on a trestle. The sun was usually hot enough to heat the drums enough to provide lukewarm showers.

As the road construction progressed, other military units moved forward in unison with the 591st. Elements of the 101st Airborne made clearing sweeps in the mountains and valleys along the route. Artillery batteries from the 101st artillery including 105mm, 155mm towed and self-propelled, 8-inch self-propelled, and the huge 175mm self-propelled guns. These leapfrogged forward as firebases were established.

All of these units required heavy resupply efforts, the beans-and-bullets necessary for the mission. Needless to say, the road travelled by frequent convoys was, at times, a hazardous place. Mines, snipers, and ambushes occurred even with the best of defensive efforts of armored gun trucks, personnel carriers, and the occasional tanks in addition to the ubiquitous helicopter air cover.

Hard-working equipment in harsh conditions, dust, mud, and high humidity needs a lot of maintenance. All of the maintenance on the 591st Engineers equipment was done under “field conditions,” that is, in the dust, mud, and high humidity.

It was not uncommon to pull and replace D7 Caterpillar engines or final drives, or truck power packs as the construction went on nearby. Frequently, “field expedient” kept the equipment running. Some of the cabs on the D7s were adorned with scrounged sheet metal. These provided some protection for the operator and critical components from hostile fire. This ingenuity truly exemplified the commitment to the 591st unit motto: “Drive On.”

Dave said, ‘We un-assed from the vehicles to see where the fire was coming from. In the excitement, some of us didn’t take very good cover. Fortunately, it must have been a guy that sprayed his magazine and bugged out.”

Recollections:

Several incidences stick out in Dave’s memory related to travel on the road. For example, a vehicle in which he was riding struck a landmine. It blew him off, throwing him into the ditch. With sporadic, incoming rifle fire, a medic sat on Dave’s chest to stitch up the deep gash in his head — of course, without the benefit of any pain killer other than adrenalin. In another situation, a UH-1 slick, the primary utility helicopter in Vietnam, was carrying a “higher” engineer officer over the area at a very low altitude. Although the pilot was warned, the helicopter struck a wire, crashed, and burned. Not everyone was able to exit the crashed bird.

Dave and his “bunker buddy” were transporting a Cat road grader on a lowboy when the recently installed brakes failed. They took a wild ride down the mountain before crashing into the river below. Fortunately, there were no serious injuries. The equipment was salvaged. Monsoon rainstorms can be difficult to describe. It did occasionally rain hard enough that in the daytime, you could hold your hand out at arm’s length and not see it for several minutes. Meanwhile, the water would accumulate around your feet — on flat ground — to ankle depth!

Not all helicopter crashes were shot-downs. A few minutes before the photo was snapped, this HU-1 slick was low leveling when it hit a wire. Unfortunately, not all of the crew made it out alive. Note the M35 cargo truck in background.

Bunkers would fill with water. Every low spot would become a pond, malaria-carrying mosquitoes would thrive, and fungus would grow on your feet (and other dark places on your body). Mud would get like grease, causing vehicles to slide off the road. Even the snakes would try to find some high ground.

During one period, a platoon of M48 tanks provided security for the 591st and other co-located elements. For whatever reason, some of the tankers were unhappy with the location of their M2 50 cal. mounts. They did not receive satisfaction from their own motor pool, so Dave, a civilian-certified welder, volunteered to have a go at it.

His buddy, Bob, scrounged some appropriate welding rod for Dave to cut and weld the M2 mounts as desired by the tankers. The welds held when the previous ones didn’t. The tankers were so happy that they kept Dave and Bob supplied with beer during their short, combined tenure.

Since the time when he was a kid, Dave was a phenomenal shot. The army recognized that ability and sent him to sniper school. An incident — almost beyond belief — occurred one evening.

The VC were probing the platoon’s position. After a lengthy exchange of fire, one of the VC stood up and ran to the rear. Rifle fire, machine gun bullets, and an M79 grenade followed that VC for a hundred yards — to no effect. The guys watched in disbelief as the fire slowed down and stopped. They broke out cheering as that VC ran out of sight.

Human congregations quickly tended to draw rats. After days of trying to trap or poison rats, Dave scared the heck out of his bunker mates by waking them with gunfire. He was using a red-lensed flashlight and his 1917 Colt Service revolver to successfully pop a few. After threats were made, Dave ended all future rat eradication by gunfire inside of inhabited bunkers.

A crazy coincidence occurred one evening. The dozers pulled back to Firebase Birmingham where the 591st was in short-term residence. Dave walked over to the stream to wash up and saw a guy he had known since the second grade and called, “brother.”

Don Tegtmeier was in the 101st Airborne as a loader on a 105 mm gun. At that time, they didn’t know that the other was in Vietnam. After chatting for a few minutes, they got a fire mission, and Dave watched as Don loaded his gun for a maximum effort shoot. Then, Don watched as Dave pulled motor stables maintenance on his D7.

They got to spend a few evenings together on the bunker line watching the perimeter. They told farm and school stories and speculated on who else from their very small high school class might be “in country.”

As it turned out, I — the author of this piece— was the third spoke of this “brotherhood trio.” Unknown to the other two, I was in Vietnam in the south.

Dave and Don soon parted as the road moved forward and the battery leapfrogged out. The three of us were able to reunite 18 months later back in “the world.”

After the War:

With roots that can be traced back to WWII, the 591st Engineer Company (Light Equipment) was inactivated in Vietnam on 1 January 1972 (the Company was reactivated 16 September, 2007 at Fort Campbell, Kentucky). The 591st was awarded unit citations during Dave’s tenure; Two Meritorious Unit Commendations and the RVN Civil Actions Honor Medal, First Class.

A pair of ARVN (Army, Republic of Vietnam) dump trucks. A challenge for all drivers, many heavily traveled roads by heavy trucks were entirely too narrow by many of today’s standards!

Like most Vietnam veterans, Dave had arrived in Vietnam by himself as a replacement into his Company. He found his niche therein, did his duty assignment to the best of his ability, and, after 16 months (he extended his in-country tour to get an “early out”), Dave left Vietnam — by himself.

He returned home and went back to the family farm. He had no further contact with his military comrades. Though he suffered from what has come to be known as PTSD and from the effects of the defoliants, he only recently turned to the Veterans Administration for assistance.

Dave’s intent with this photo was to show that when supplies were needed, it wasn’t an easy trip down to NAPA or AutoZone. Material was packaged in waterproofed paper and boxes and frequently then placed in plastic bags, then nailed in wood boxes and loaded into steel shipping containers called CONEXs.

Dave visited the Engineer Museum at Ft. Leonard Wood, Missouri, during the 2017 Route 66 MVPA Convoy and was surprised to find an exact duplicate of “his baby,” a Vietnam-era D7E with cage and plow.

Dave Flinn found an exact duplicate of “his baby” — a Vietnam-era D7E Caterpillar dozer at Ft Leonard Wood, Missouri, during the 2017 MVPA Route 66 Convoy. Photo by Mark Sigrist

Dave Flinn was killed in December 2018, when a van ran a stop sign and hit him. Thus, what is have written here was dredged up from small fragments of memory of past conversations. Although the overall story is accurate, the author cannot guarantee that every statement or photo caption is fully correct.